#12 - 🎵 There's a limit to your love... 🎵

The fences and hurdles that shape our care and connection.

Hello there, 👋🏼

Life™️ keeps happening, which is slowing down the writing process a little at the moment. I have a head full of ideas, but unfortunately, the nature of specialisation means that getting them out into the world requires delegating to two departments that are often otherwise occupied or overwhelmed. Namely, my brain’s executive function, which is faced with the daunting task of translating the swirling mess to RegularHumanSpeak™️ and my body, which for some strange reason isn't typing as quickly as usual on the other side of a pretty gnarly table saw injury.

Thanks for your patience!

If you’re new here, it might be helpful to know that the initial phase of this project is designed somewhat sequentially, building one idea on another and expanding as we go. If you find this piece helpful, starting from the start might a good idea.

Take care!

Shane.

Redlining Expected Productivity.

Last newsletter I discussed BRV’s observation of the rise of self-blame within his clients. With the onset of neoliberalism in the 1970s, there has been a slow withdrawal of resources from society — and it’s not just financial.

Productivity has gone up, but real wages have gone down.1 Care and connection needs haven’t diminished, but the available time and energy our society has to meet them has shrunk. There are new limits to our love, and while this is liberating for many who have carried more than their fair share of the load, at a societal level, we are all suffering for it.2

In fact, I’d argue that the level of care we aim to provide has actually increased as we’ve aimed to create a more understanding and compassionate world that gives more dignity to those experiencing aging, disability, neurodiversity, trauma and a whole host of other experiences.

Seeing the work teachers at our kid’s school do to accommodate neurodivergence, educate about diversity, foster kindness towards difference, and cultivate empathy on top of academic education (while not resorting to throwing dusters at kids’ heads like “back in my day”) is truly remarkable.

At the same time, there are very few workplaces that do not aspire to increased sales, worker productivity, profit margins, social impact, or shareholder value. I feel like we’re being stretched both ways, and too many people I know are on the verge of breaking yet cannot allow themselves to falter in a system that punishes those who cannot produce.

The other day, a friend who has been struggling post-concussion remarked that it’d better come right soon because if it took another couple of months to recover (as it well could), it’d create some pretty serious problems for his work. Which, on the one hand, is absolutely, totally understandable. But on the other, is also incredibly revealing of the world we have been socialised into, where there are serious consequences if we cannot perform or produce at our peak for any length of time.

It's almost as though capitalism has convinced us that our bodies are finely tuned productivity machines rather than fragile living organisms. Which continues to leave us in shock and dismay when faced with a downturn.

I always wonder how previous generations of human existence have perceived such experiences. Did they, too, see these as completely unexpected, unacceptable and impermissible events?

I doubt it Gary.

Losing the lottery.

There are all too many ways of losing in the neoliberal lottery: wrong race, wrong neighbourhood, wrong body, wrong gender, wrong location, wrong background, wrong age… you’re a very slim chance of “winning” the life of our collective dreams. It turns out that some of us were born with infinitely fewer tickets than others.

There are a million different ways this plays out, so forgive me for another anecdote about my family. This is not a disability and parenting newsletter, after all, but it’s the one I know best right now.

As someone who has largely held an abundance of tickets most of my life, what has interested me recently is my response to a small win in a season where I’ve held far fewer.

As I mentioned in a previous newsletter, after hundreds of hours, many tears of frustration, and multiple years of fighting, we finally managed to get the kind of government-funded support (NDIS) for our disabled child that would allow our family to live two steps back from the cliff edge and have periods of time where we’re not playing what we call “mental health chicken” (a super fun game where you work out which parent is closest to a breakdown so the other partner adds even more load to their pile in an attempt to buy them more time).3

I’ve got to be honest: amidst the frustration, joy, rage, relief and exhaustion, when help finally arrived, what genuinely surprised me was the guilt.

It costs a lot of money to keep our family together.4 A LOT. When our NDIS package was finally revised, the number attached to it was staggering. I felt awful for all of the other people needing support and found myself questioning whether we really needed this much.5 Which, given we’d spent three years hanging by a thread in almost every capacity, is quite telling.

A fair amount of our support goes to highly trained therapists who can help us work with the limitations of our child’s ability to regulate his nervous system, but by far the highest figure goes to the heroic support workers who we share our lives with seven days a week. Our son effectively requires someone to give him almost undivided attention for the vast majority of his waking hours. There is no nuclear family on planet Earth who can provide this, let alone while holding down jobs, caring for their other kid, or retaining their sanity. Trust me, we’ve tried.

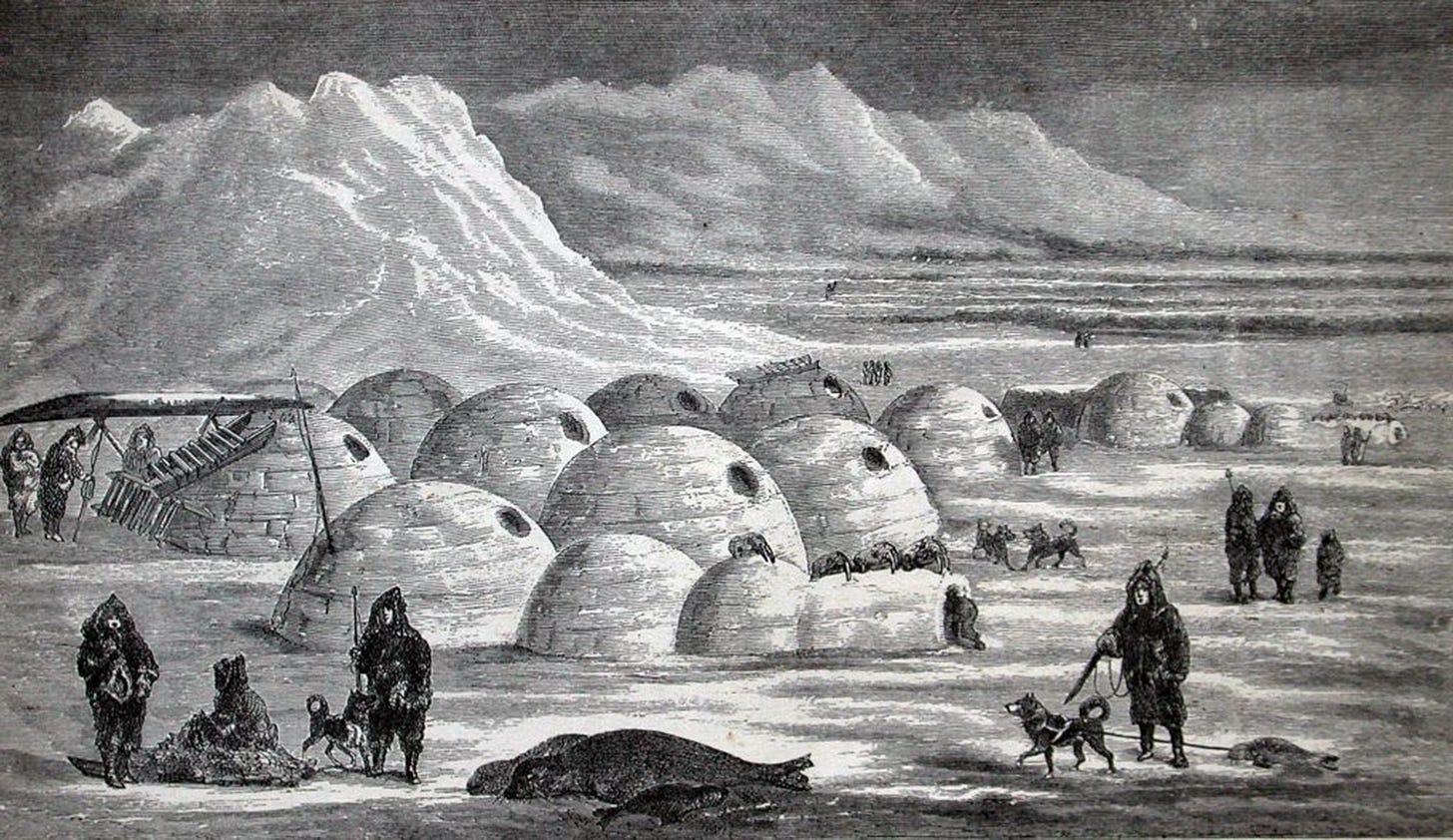

In most contexts throughout human history, these care needs would not have fallen on two people. In some cultures, it would be skewed along gender lines, in others less so,6 but the idea of two people caring for the complex needs of their offspring (and simultaneously, their own bodies, aging parents, and sick friends) would be unthinkable.

Fenced and Siphoned.

So where has all the care gone? We’ll expand on these ideas as we go, but one way of thinking about understanding the way care has changed under capitalism is that our sphere of expected responsibility has been reduced, and our human energy has been redirected.

Fenced: Limitation of responsibility.

For much of human history, other people were close by whether you liked it or not. Nomadic people moved together. Villagers might foray on expeditions for trading or hunting, but the majority of human life and effort was spent in proximity to everyone else.

For most of them, “work” wasn’t somewhere you went, separate from your home or community. Kids would watch or help as you gutted a fish, wove a basket, or milked a goat. You did these activities alongside the same people you did everything else with. Elders weren’t “somewhere else”; they were right there. Dodging your neighbours was not an option. Not having kids underfoot was much harder if you didn’t construct a barbed-wire-wrapped hoola-hoop attached to braces that you wore at all times.7

Was this less efficient? In terms of production, absolutely. But in terms of meeting human need, it's highly doubtful.

Our homes and workplaces are now metaphorically — and often physically — “fenced-off”. The constructs of “the nuclear family” and “going to work” create clear boundaries around who is expected to care for who, and where care happens and where it doesn’t. Parents must care for young children, and partners for each other. Friends have some responsibility, depending on how close they are. But after that, it's all a bit of a crapshoot.

One thing’s for sure: work and care are almost always pitted against each other. It might be a helpful time to remember that I'm not against work or productivity in themselves. They can both be incredibly meaningful and fulfilling parts of life. My issue is what happens when the pursuit of profit enters the equation and begins to dismantle the brakes, leading to a point where we no longer know how to justify slowing down.

In addition to this, we’re losing shared spaces where whole collectives of people can see who’s missing, who’s celebrating, and who’s struggling. Where needs are noticed simply by virtue of existing alongside each other and met because of a general sense of mutual obligation.

This means that care and connection are rarely “on hand” any longer; they’re administrated, negotiated and requested.

When people ask how they can help our family, the best answer I can give is to just “be around”. It’s tricky to explain, but the kind of help we need the most is usually at very short notice and with people with whom our kids are familiar. Getting help requires sending a text, waiting for a reply, working out availability, and aligning schedules, only to find it’s not a good time before repeating this with the next person.

Because of longer workdays and increasingly tight schedules, we are increasingly less “interruptable”. While it is broadly acceptable for work to bleed into the rest of our lives when required, it is far less acceptable for care and connection to do the same the other way.

All of the fences between our shared lives mean that we have to proactively engage with offers of support, even when they are genuine offers. Inviting people “over the fence” is made infinitely more difficult by a series of hurdles both parties must navigate. Most often, this is either too much energy to contemplate spending, or it takes so long to organise that the moment has passed.

The connection crisis shares similar patterns — once you’re out of a social loop, it becomes increasingly hard to administrate your way back into one. The difficulty is multiplied when you lose your confidence in making new connections, which is why all too many people report their friendship circle consists of themselves, their partner, and Netflix.

As a society, our circle of “care responsibility” has radically shrunk, and the flipside of this is that the number of people who feel they owe us care has shrunk, too. This means that living with the imminent threat of care needs and crises has become an increasingly high-stakes lottery for individuals: when they arise, the demands are concentrated on disproportionately fewer people with increasingly smaller networks.8

But before we make it sound like everyone who doesn’t have direct care responsibilities is a cold-hearted monster who just chooses not to help, we need to recognise how much harder it is to offer care and connection in a world built this way. If accessing care is tricky, offering it is, too.

This newsletter was feeling long enough already, so I’ll save the second half for next week, where I’ll discuss how care has been siphoned and why we pretend to live in a world that no longer exists.

Take care. And turn saws off before moving stock around your workshop. Just trust me on this one.

Shane.

If you already have too many subscriptions, but want to support my writing as a one off, a lovely way to do that is:

If you want to follow along, or support Untethered ongoing, Subscribe or Upgrade here:

I love hearing your thoughts and reflections, feel free to:

If you want to get in touch, send me a message:

If you want to share this post, there’s a very helpful button called:

If you enjoyed this and want to see where we’ve been, start here:

This is going to shock you to your core, but apparently the profits aren’t going to the people who do the work!

I love James Blake and I am confident that adding a link to his work will lead to him noticing this post and becoming a close personal friend. It's a solid plan.

In fact, things are so good that no professional has had to tell us “there are no other options, just call the police” in over two months!

I was told numerous times off the record that there would be a point where the Australian Government would recognise that there was a viable threat that care could be relinquished. At this point the system would shift from a defensive posture (how much can we withold and see if you can cope) to an offensive posture (how much can we provide to support you to ensure that you don’t collapse as a family unit, requiring full-time care for your child. The maths tells them this would be infinitely more expensive than any situation where you have two parents and their entire care network providing care for free). They were right.

Ironically, multinational corporations don’t seem to feel quite the same levels of shame for receiving mind-numbing levels of public sponsorship they receive (a.k.a. tax evasion).

European settlers were often confounded by the patterns of co/allo-parenting in pre-colonial Maori life: “Both parents are almost idolatrously fond of their children; and the father frequently spends a considerable portion of his time in nursing his infant, who nestles in his blanket, and is lulled to rest by some native song… The children are cheerful and lively little creatures, full of vivacity and intelligence. They pass their early years almost without restraint, amusing themselves with the various games of the country.” George French Angas (1822–1886) artist, naturalist, writer.

Patent pending.

It’s not just who we care for but also who we are responsible for caring about. Another way of saying this is asking, “Whose interests do we protect?” When it comes to how we vote, who we check in on, and who the system we build advantages, how wide is the circle we feel responsible for?

Wonderful, gorgeous, wise, brilliant!

Really appreciate where you are heading with this Shane. It’s so reassuring to know there are people like you who get that whilst care is not valued in our society as a whole, it is still of incredible value - especially to those who are in need of it!