Hi again! 👋🏼

If you’ve just joined, we’re trying to get to the bottom of why we feel Untethered, how we might feel about that, and what to do about the not-so-good stuff without falling into unhelpful binaries or shame spirals.1 This newsletter makes more sense in order, but just to help you out, this is what we’ve done so far:

-Discussed what the Untethered feeling is and acknowledged it can be simultaneously liberating and isolating.

-Reminded ourselves that this is a systemic issue, not just a personal one. We can’t shame our way out of it.

-Introduced “The Magic Window” via a glimpse into the circus that is my family and the volume of care it requires just to make it through each week.

-Explored why “care” doesn’t seem as important as “work” and discussed the way the language of capitalism shapes our everyday lives.

Today, we’re going to look at how “work” took centre stage in our culture.

The Trade-Off.

“Another way of measuring friendships is to look at reciprocal friendships. Here, the Australian surveys asked: 'How many people are there around here to whom you can turn in times of difficulty? I mean, someone you could trust, and whom you could expect real help from in times of trouble (apart from those at home?'

In 1984, the average adult had five of these reciprocal friendships. By 2018, it was down to three. Since 1984, Australians have shed four of the friends they can talk with frankly and lost two of the friends who would help them in times of trouble. On these measures, Australians today have only about half as many close friends as in the 1980s”

- Andrew Leigh and Nick Terrell, “Reconnected”.

Whether we like it or not, there is a trade-off happening. For all of the energy we expend being more productive, having highly curated communities of acquaintances, immersing ourselves in experiences and seeing more of the world, loneliness is on the rise. There are statistically fewer people we feel like we can ask for help.

One of the driving forces behind The Magic Window (TMW) is the feeling that there is a limited amount of time when we get to really live, chase our dreams, and make our mark. There is a vision of life on offer under capitalism where life isn’t just wading our way through some generic mundane existence filled with chores and obligations but instead carries some ineffable quality, a sense of vitality that will make our life really mean something.

There are plenty of different versions of this idealised life: securing our financial future, making a name for ourselves, exploring the world, climbing the corporate and status ladders or cementing a personal brand that garners the respect of our peers. (Ironically, the pot of gold at the end of TMW — to mangle metaphors — is often a fantasy involving a lifestyle without work or any other obligation.) We chase these dreams while subconsciously knowing that, at any moment, it can all be snatched away from us.

It’s not that we can’t do these things in other seasons of life, but that we instinctively understand that it gets much harder when muddied with other responsibilities. So we actively work on remaining as Untethered as manageable by minimising the “obligation baggage” we accumulate along the way.

A big part of TMW mythology is that we are both entitled to it and require it. We feel entitled to it because this is “living the dream”, and it’s incessantly sold to us through advertising, biographies about life’s winners, and the conditioning that comes through scrolling through endless depictions of everyone’s #blessed lives. We are convinced we require it because unless we use this unencumbered time to secure our future, we have been taught that we can’t rely on anyone else to secure it for us.

We’ll unpack this later, but it’s worth noting here that how aware we are of the possibility of TMW closing is often strongly affected by gender expectations. Because societal care expectations are higher for women, they often have a stronger sense of the limited amount of uncluttered time on offer, particularly if they envisage having children. Men are more likely to be caught by surprise by the closing of the window or find countless ways of outsourcing or evading its impact.

Today, I want to further explore the origins of why we culturally value some things over others. In particular: “work/productivity” over “the rest of life”. Warning: I’m going to use a lot of generalisations to make a point here:

Why does introducing yourself as an entrepreneur at a party feel more interesting than as a stay-at-home parent?

Why do aged-care staff generally get paid less than corporate accountants?

Why do we push through a thumping headache to get a work project completed after hours but skip hanging with friends because we’re too exhausted from work?

Why does being unemployed carry a social stigma, yet working 80 hours a week doesn’t?

Why do we feel so guilty when we rest?

Why do men, in particular, face such huge identity crises when they retire?

To understand these feelings, we need to discuss how "paid work” became paid work, why doing paid work is perceived as “productive”, and why being productive is seen as more valuable and of higher status than the one thousand other ways we can use our time. I mentioned earlier that I think capitalism is both an economic system and a social imaginary. This is one part of the story of how that came to be.

Growth is Good?

We hear a lot about the state of the economy: interest rates, stock market booms and busts, housing prices soaring, rising inflation, and tracking the GDP. Even if you pay no attention, it’s likely that you’re familiar with one particular phrase: economic growth. If there’s one thing that we’re all supposed to know about the economy, one universal truth, it’s that GROWTH IS GOOD.

There are a bunch of ways of measuring this, but the bottom line is that what matters economically for each nation state is that they keep increasing what they can produce, consume and measure their wealth by. You may have heard the term “Gross Domestic Product”, which is a way of counting what a country has “produced” in any given year.2 The goal is growth. Endless growth. When this graph goes up, we’re doing well. When it goes down — bad, bad, bad.3

What exactly fits inside the economy? While GDP includes investments and a bunch of other stuff, it largely boils down to goods and services that people pay for — i.e. stuff that’s a product of what we consider “work”. Given that we all expend energy on a thousand different things in life, why is it that we all pretty much agree that "real work” is doing stuff that you get paid for?

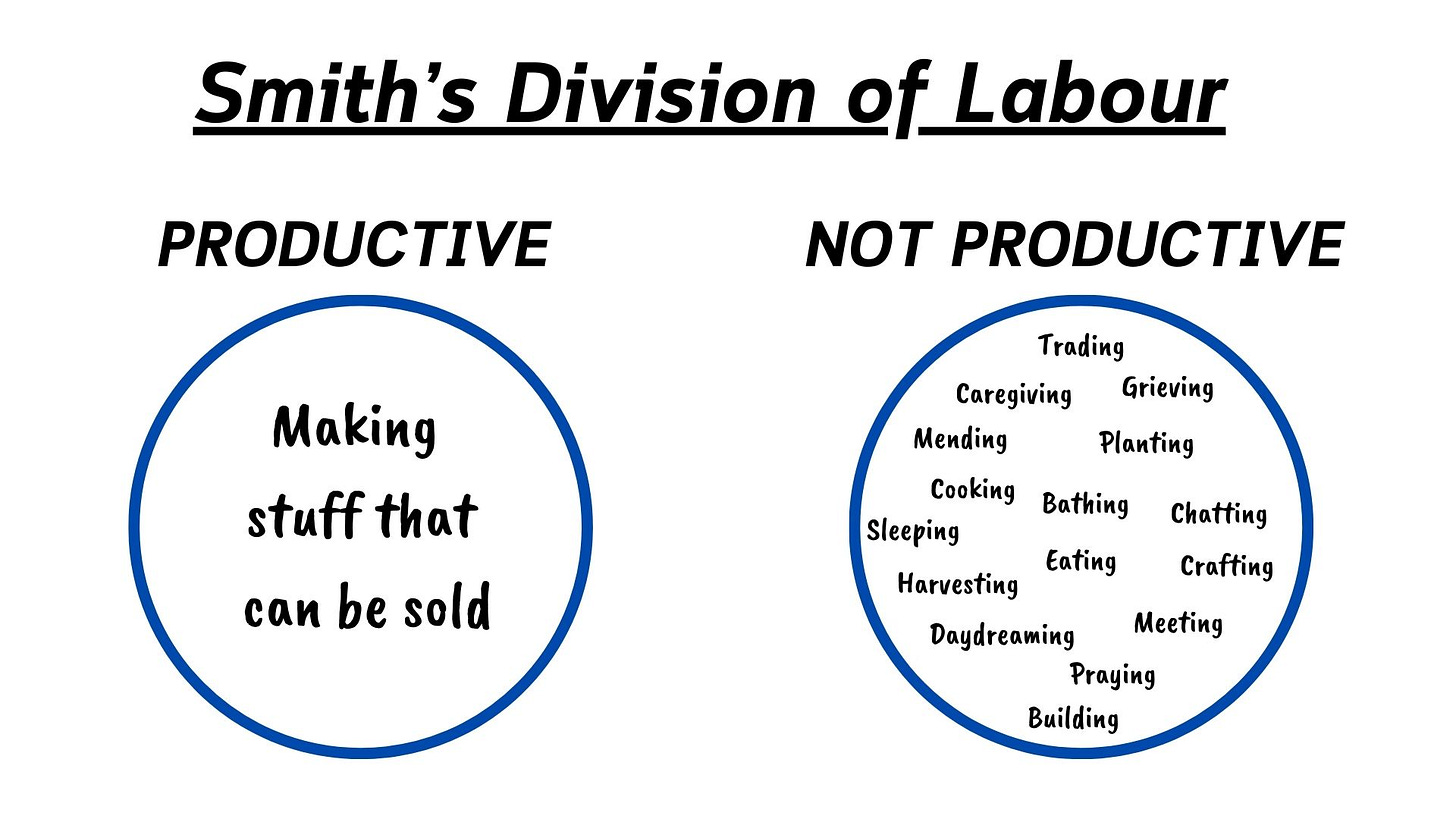

To understand this, we’ll have to go back to Adam Smith, the father of capitalism and his gargantuan treatise “The Wealth of Nations”.4 To save you from wading through its 304,000 words, all you need to understand for today is that he proposed that for nations to advance economically, they needed to focus on what they could produce.

Smith was writing from Scotland around the time of the Industrial Revolution. Britain was moving from an agricultural society (lots of labour-intensive subsistence farming and homespun clothing) to an industrial one (lots of steelworks, factories and mass production). He was trying to describe this new economic landscape and show how countries could make the most of it.

To get ahead, he proposed, countries shouldn’t just store up huge piles of gold but invest in production. It's kind of like the difference between putting your money under a mattress and investing in a candy floss machine. In the short term, you’ll be cash-poor, but in the long term, you’ve found a way to continue increasing your wealth-building capacity by producing something that others want to buy.5

To make the kind of “progress” that would secure a nation’s future and fund a military large enough to protect itself (read: stop others violently taking what you had violently taken), Smith realised that enough was not enough. Making a profit meant creating excess, which could be sold into ever-expanding global markets. What came to be deemed productive was excess worth paying for. Production took more than just financial capital; it required redirecting enormous masses of human energy.

In agricultural societies, there wasn’t much point in overproducing food and livestock, busting a gut to create mountains of excess made no sense. You needed enough to get you through the seasons and a little more stored up just in case things took a turn. Then you’d just “waste time” hanging out with loved ones, caring for children, contemplating the divine, and sitting peacefully by a river thinking about things while staring in wonder at the sunset. 🤮

But with Smith’s proposal, you could get ahead by creating excess goods and services that could be sold for profit.6 Increasing profits meant separating out what was “productive” (making stuff that could be sold) from what was “unproductive” (doing stuff that had no value as soon as the effort was expended).

So people moved en-masse from the country to the cities to work in factories and participate in efficiently creating excess. Men, women and children were hoovered up. Blood, sweat, and tears were fed into the system, moving more human activity further from home.7 Working hours got longer, and every spare moment of time was absorbed to “maximise production” and make more stuff faster and cheaper than their competitors.

Again, Smith didn’t view unproductive activity as bad or unimportant; he just meant it wasn’t going to enable the nation to produce more. He didn’t even include his profession as an academic in “the market”.

But as time rolled on, people decided that men of letters really should be included in the market — after all, they weren’t going to do it for free. Not like raising a child or caring for an elderly neighbour — you know, all those things that just happen invisibly in the background because they’re done for love, and they’re really not that hard…

Over time, this shift continued, with our vision of “the market” slowly absorbing practically anything that people deemed worth paying for. But those fault lines remain between what is deemed “productive” and what isn’t, what human effort deserves monetary reward, and what doesn’t. Between “the workplace” and the private sphere.

Not only that, this vision has sucked an extraordinary amount of human energy away from what was once known as the stuff of life and funnelled it into creating profit.

The Black Hole of Capitalism.

So what does all this have to do with feeling Untethered? Well, fast-forward 250 years, and these ideas have not just stuck, they’ve flourished. They’ve become so much a part of the background of our culture that we find it hard to imagine there’s any other way of seeing the world.

They have attuned us to prioritising productivity over play, rest, stillness, and connection.8 They’ve shaped who we think is a “lifter” and who is a “leaner”, who is worthy of care and who isn’t, who deserves a home and food and dignity and who should have to scrape and suffer to access them.

Somewhere, deep in our psyche, “being productive” is useful, meaningful, exciting and high status. The rest of life must be justified against this. So the currents of capitalism pull our energy towards the economy and slowly suck the marrow out of the rest of our lives. And the way the profits of our labour are distributed only cements this reality.

Gross Domestic Product goes up up up!

But what happens to Gross Domestic Care, Gross Domestic Connection, Gross Domestic Play, Gross Domestic Rest, and Gross Domestic Daydreaming…?

Until next time, take care.

Shane.

If you already have too many subscriptions, but want to support my writing as a one off, a lovely way to do that is:

If you want to follow along, or support Untethered ongoing, Subscribe or Upgrade here:

I love hearing your thoughts and reflections, feel free to:

If you want to get in touch, send me a message:

If you want to share this post, there’s a very helpful button called:

If you enjoyed this and want to see where we’ve been, start here:

Try harder! Join a commune! Do better!

GDP is a way of measuring a country’s total production of goods and services.

But who to blame? The reserve bank? The current government? The last government? The unemployed for not producing? The employed for driving up interest rates? Environmentalists and Indigenous folks for trying to slow us down? More on that later.

I have a lot to say about him in future newsletters. While there are very good reasons to be very annoyed at Smith, understanding his context and core assumptions might help us rethink him. To keep this simple for now, I’m not going to differentiate between what I believe Smith originally intended and how his work has come to be understood and used in our time. This is a newsletter, after all, not a history book.

Hot investment tip: candy floss is delicious!

While taxes, levies, conscription and the brutal treatment of slaves and serfs have been a part of empire-building for a good chunk of human history, the general vibe was that those in charge skimmed from what was already being produced. While markets and trade had existed for centuries, the aim of maximising the production of an entire nation for domestic and international exchange was a foreign concept — and life (family structures, daily activity, etc.) mirrored this.

For balance, it’s worth noting that not everyone experienced this shift negatively. Some report that the move to the cities and the increased personal wealth and liberty that came from working in factories was better and more enjoyable than the toil of serfdom.

No one would deny these matter, it’s just that they must be squeezed around a productive life. Go to the gym at 5 am! See your friends on the weekend if you haven’t collapsed into a catatonic week after work has extracted every ounce of energy and the very will to live out of you. Even take up a hobby — or even better, a hobby that you can capitalise by turning into a side hustle!

Thanks Shane, keep writing and making us think about this stuff, it’s very necessary. We need more minds like yours in this world!

More like ‘Madman’ Smith. Can’t believe people think a 250 year old book — which was written as a defence of selfishness by a man who lived with his mum as an adult and thought humans were incapable of moral judgements and who on his deathbed was sad because he hadn’t worked more — bares any semblance of the world in 2024. What a chump. What a bunch of chumps.