#15 - I didn't mug a child - do I get a prize yet?

What if we owe the world more than our work?

Over the last few newsletters, I’ve proposed that some of the major obstacles we face when seeking care and connection are:

The fences of perceived responsibility: Who am I responsible for? And who is responsible for me? My nuclear family? To a lesser degree, my friends? And after that?

The hurdles that we have to jump: aligning busy schedules, initiating new connections, and overcoming the feelings of vulnerability that come with asking for help.

The shrinking margins of “interuptibility”: The limited social, emotional and administrative energy remaining after fulfilling our work and kinship obligations.

A lot of what we’re discussing is an implicit social contract - the unspoken agreements we share about what we owe each other, and the kind of life we can expect to have.

We’ve covered this at length, but to summarise, there’s a general sense under capitalism that if you work hard and choose well, you’ll be rewarded with a secure life, a house at the end of it, and a couple of decades of carefree retirement. You take care of your work, your personal needs, and your family, and everything else will take care of itself. But the credibility of this story — which never actually worked for all too many people — is creaking at the seams.

How much do I owe?

One of the core reasons is that it is built on another fundamental social contract — this time about what we won’t do: harm each other. While it may feel like a universally accepted and common-sense idea, “do no harm”, especially when applied to those outside your kin, is in fact a contested and radical concept across human history.1 Yet it is one that most of us would feel we subscribe to. I mean, we don’t teach our kids to go out of their way to intentionally hurt people.

“Do no harm” is a negative rights ethic, referring to what we each are entitled to be protected from. And while this is an important first step, many argue it’s just not enough. On its own, it can feed a narrative that as long as we’re not actively going out of our way to hurt others, we’re doing our bit, and everyone will be fine.

This story presupposes the myth of self-sufficiency: that everyone, with the right attitude and enough pulling up by bootstraps, can ensure all of their own needs are met. Which is, of course, ridiculous when you say it out loud.

On top of that, it again hides the effort required to initiate and maintain care and connection. The hidden subtext of our culture says, “You owe the world work/productivity”. But it does nothing to outline our responsibility to maintain the living human web. Those with limited capacity to produce do not have their inherent worth and dignity acknowledged. Those who carry more than their share of care and connection are overlooked. And those who shirk tending to the social glue that binds us are valorised without acknowledging the debt they owe to those who hold the rest of the world together.

To create a better world, we need a better story and a better ethic. We need to tap into a better story, a more robust ethical framework than one that centres scarcity, competition and individualism.

You’re not a mushroom.

Feminist ethicists such as Sandra Sullivan-Dunbar, Eva Kittay, and Cristina Traina propose that we begin our ethical task with the idea that “everyone deserves care”.

A pioneering voice has been that of Eva Feder Kittay, who writes from her experience as mother to Sesha, a daughter with profound cognitive disabilities.

Kittay proposes a relational understanding of equality: our moral equality, our entitlement to inclusion within the scope of justice, lies not in any particular capacity but in our status as “some mother’s child.” We have each received the attention and care of a “mothering person” (not necessarily a woman or our own biological mother) in order to survive to adulthood; some person has considered us worthy of such attention and care.

Sullivan-Dunbar, Human Dependency and Christian Ethics, 225.

This is called a “positive rights” ethic, and makes the claim that we not only should every human be protected from harm, but there are certain things that they should be provided too.

Which all sounds lovely (and it is!), until you begin to explore the flipside. If we were all once freely given care, could it be that we may owe the world more than just hard work? Perhaps, to the degree we are able to repay it, we each owe the world a debt of care.

This, of course, is a lot more effort and a lot more inconvenient than just not harming others. In this vision, we can’t see a lost child on the street and walk past while congratulating ourselves for not kicking them, or stealing their backpack of snacks. As a collective, we are all responsible for making sure they are helped.

As Sullivan Dunbar states: “Dependent care is a positive moral effort, not primarily a restraint from harm.”2

What it comes down to is recognising that we were brought into the world by care. None of us “sprouted up like mushrooms.”3 Except in the most tragic of circumstances, we were all held, fed, cooed over, and nurtured.4

To claim that our only debt to the world is backbreaking labour, profit-making innovation, and a ruthless ascent of the social and corporate ladder is to undermine the intimate, intricate and deeply personal care that carried us into adulthood in the first place.

“Approaching the problem of dependency through self- interest starts at the wrong point, from the autonomous adult, not as we do chronologically, from the standpoint of neediness and indebtedness.”

-Sandra Sullivan-Dunbar

Yes, you are a burden. Get used to it.

We have built a society that systematically and socially punishes a lack of contribution to the market. But we don’t do the same with care and connection. This makes “spending” your time caring, committing to collective life, and prioritising connection a difficult and risky investment.

Yet, when I think about the friends, family, and community members with whom I share all of life’s hysterical laughter, painful confession, deep love, crushing loss and mundane reality, I know I want more of this in the world. I want to build a world that rewards this and funnels our resources in a way that makes this possible.

If we are to continue to survive as a species and as a planet, it will be through siphoning human energy back towards a way of being that ensures we don’t all have to produce at maximum capacity until the day we collapse in a heap.

Whenever people express that they don’t want to feel like a burden, after admitting that I share their sentiment, I try to remind them that we are all burdens, whether we realise it or not.5 To be a human is to be a burden, an inconvenience, and more times than we’d like to admit, a pain in the ass. But the person who is never inconvenient or inconvenienced is a truly tragic figure.

Positive rights ethics have the capacity to stretch us in both directions. On one hand, they might help us to value, prioritise and take more responsibility for care and connection. And on the other, to allow ourselves to ask for them, receive them, and believe that we are worthy of them.

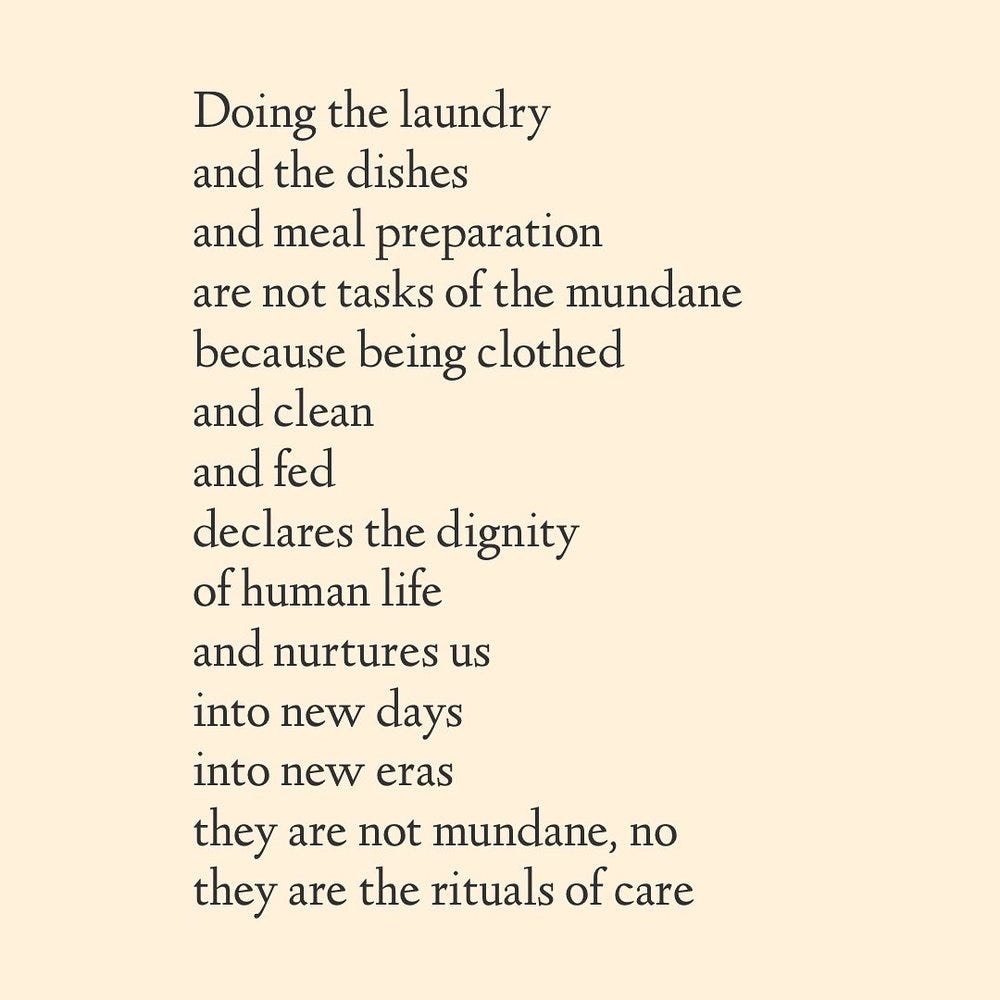

I’ve had to make this a practice in my life, constantly reminding myself that doing the dishes, having a nap, playing with my boys, reaching out to friends, and switching off my “work” brain at home is not wasted time. In fact, I owe it to the world. It’s a new discipline, but I am trying to take equal pride in my unpaid labour as my paid labour.

Having space for care and connection relies on having margins in life. Under capitalism, margins are wasted time, wasted potential, and wasted opportunity for growth and grind. But under a different vision, these margins make room for life itself.

Take care,

Shane.

If you already have too many subscriptions, but want to support my writing as a one off, a lovely way to do that is:

If you want to follow along, or support Untethered ongoing, Subscribe or Upgrade here:

I love hearing your thoughts and reflections, feel free to:

If you want to get in touch, send me a message:

If you want to share this post, there’s a very helpful button called:

If you enjoyed this and want to see where we’ve been, start here:

And one that gets very complicated, very quickly, when it comes to defining where it should apply.

Sullivan-Dunbar, Human Dependency and Christian Ethics, 175.

You guessed it, another Sullivan Dunbar zinger.

And if, for some horrific reason, we were not, we all deserved to be.

“I cannot do everything for myself, even if virtually everything that is done for me is a thing I could do. Furthermore, even if each of us could grow our own food, build our own houses, transport ourselves without using the roads, cars, and trains built and maintained by others, virtually none of us are doing so. Yet those with the most privilege think of themselves as independent anyway, and this mythology becomes an excuse for their privilege.

In reality, dependency is more universal, more foundational, and more pervasive than autonomy.” - Sullivan-Dunbar, Human Dependency and Christian Ethics.

Love these thoughts Shane, thank you.

Oh wow, this is all I’ve been thinking about lately. What are my responsibilities? Where am I disconnected from community/care? What suffering does my comfort cause?