#7 - Lifters, Leaners, and Social Glue.

Who's picking up the bill for the cost of production?

“They’re a burden on society that too many of us are shouldering, just so they can escape real work — we shouldn’t stand for it any longer. They’re leeches and freeloaders, and a drain on the system. All they do is take.”

— Possibly your Uncle, talking about beneficiaries, immigrants, or anyone else he feels like having a pop at.

What does maximising productivity really cost us?

Community takes effort. Checking in takes effort. Maintaining connections takes effort. Heck, even just trying to get a crew together for a shared meal takes a bunch of effort. Without a connection to the living human web, our communal life begins to slowly shrivel.

Yet it feels like “productivity” has the right of way in our culture. There is little cultural resistance to taking on a promotion with more hours, doing overtime, or monetising that hobby by turning it into a side project.

One of the questions I asked in the last post was why there is a negative social stigma about being unemployed but not about working 80 hours a week.

Obviously, it’s a complex question with a long history, and a lot of nuance is required, but at least part of the story is the fear of being perceived as not contributing to society, not earning your keep, not producing your fair share. As we discussed, our perception of what is deemed productive and, therefore, “a real contribution” is deeply distorted.

Viewing paid work as the most valuable gift any person can add to the world is grim at best. Yet, when we think about an 80-hour week, we can’t help thinking about how much that person is doing — what’s unlikely to cross our mind is how much that person isn’t doing.1 Not just for themselves but for everyone else too.

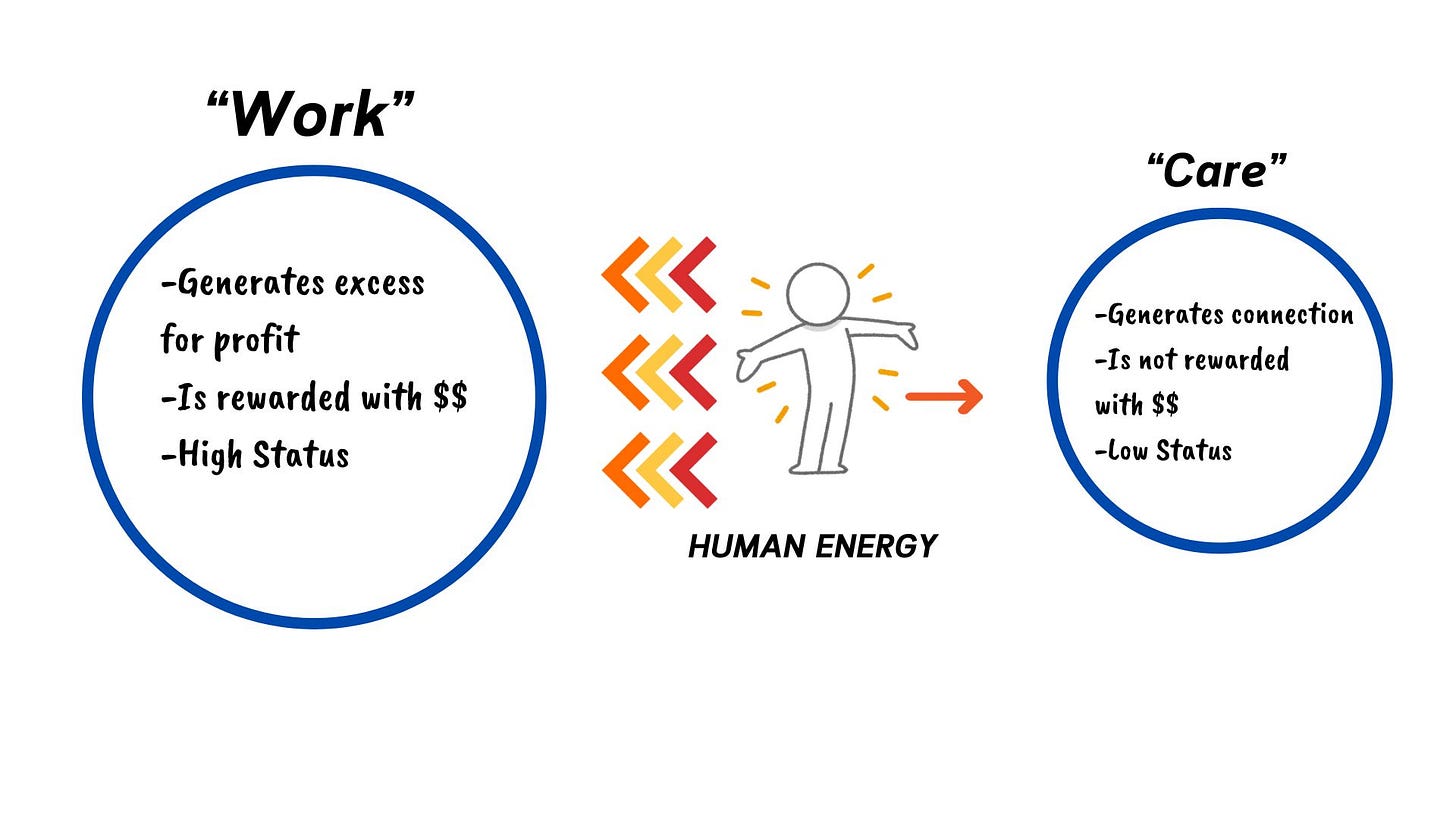

When we reflect on the way human energy under capitalism has been diverted towards generating excess for profit (and therefore away from the rest of life), we’re not just talking about time. We’re talking about energy, too: physical, emotional, and social. Workplaces under capitalism, with their drive for productivity, efficiency and meeting KPI’s tend to drain us of every available human “resource” during the time they have us.

While it’s unhelpful to generalise too much about historical eras of work wholesale — I’m sure building pyramids was no walk in the park — economic anthropologist

highlights how modern working conditions may be taking more than we realise:"There's more to work than the amount of time spent doing it. Carving a wooden door frame for ten hours in the 1600s is a very different emotional experience to jumping between a hundred emails, meetings and micro-tasks for four hours in 2023. Levels of workplace burnout have skyrocketed. We might think we've escaped Charles Dickens 19th century sweatshop dystopia, but our global economy now apportions drudge-work to labourers in the Global South while middle-class workers plug into an attention-burning digital matrix that yokes us far beyond ordinary work hours."

—Brett Scott, Tech doesn't make our lives easier. It makes them faster.

What work requires is not just time but attention, emotional energy, headspace, creativity, social capacity and a whole lot more. With the modern drive for efficiency and productivity squeezing every drop from employees, it’s worth asking what’s left of their capabilities in life outside of “work”?

If all that energy is going to production, where is it being redirected from?

Obviously, Gross Domestic Napping, Gross Domestic Play, Gross Domestic Folk Dancing, Gross Domestic Slow Walks in Nature and Gross Domestic Whittling are in sharp decline.

But how does all of this impact our ability to remain connected to each other and participate in the Living Human Web? We may be giving work our all, but who’s picking up the bill?

Social Reproduction, Social Glue.

Despite the name, social reproduction is not about casually having kids with random friends. That’s generally a terrible idea. It’s an area within anthropology that studies the ways social systems are maintained and continued.

Feminist philosopher Nancy Fraser homes in on the way that one critical element has changed under capitalism — the social bonds that connect communities together:

“Social reproduction is about the creation and maintenance of social bonds. One part of this has to do with the ties between the generations—so, birthing and raising children and caring for the elderly. Another part is about sustaining horizontal ties among friends, family, neighborhoods, and community. This sort of activity is absolutely essential to society.

Simultaneously affective and material, it supplies the “social glue” that underpins social cooperation. Without it, there would be no social organization—no economy, no polity, no culture. Historically, social reproduction has been gendered. The lion’s share of responsibility for it has been assigned to women, although men have always performed some of it too.”

— Nancy Fraser interviewed in Dissent.

When we think about the idea of feeling Untethered, we may be overlooking the fact that historically, social reproduction has been rendered invisible in our system because it hasn’t been financially or socially rewarded. Popping over to hang up the washing for an elderly neighbour, making a casserole for an unwell relative, organising a kid’s birthday party, taking a relative to chemo, checking in on a friend you’re worried about to make sure they’re doing okay — many of these are things that require “spare” time, and energy — in addition to an emotional investment in others.2 As someone who is without a doubt being sticky-taped together each week by a remarkable group of friends, I cannot overstate how critical this care is.3

None of these things are rewarded financially, but they’re also way down the food chain status-wise. While people might think it’s kind you stayed home with a sick kid, they’re more likely to pity you than brag to their friends about the fact they know someone so impressive and important.

If staying connected is essential, and each of us needs at least 50 people to flourish, then who is doing that work to foster that community and maintain those bonds?

We have a supply chain issue!

Fraser goes on:

In capitalist societies, the capacities available for social reproduction are accorded no monetized value. They are taken for granted, treated as free and infinitely available “gifts,” which require no attention or replenishment. It’s assumed that there will always be sufficient energies to sustain the social connections on which economic production, and society more generally, depend.

And there aren’t. Involvement in collectives — which used to hold us together — has been in steep decline since the 1970s. There are many reasons for this, free time included, but I believe that the energy we have left over after juggling “productive work weeks” and everything it takes to “adult”, we have little left. I have a friend who talks about missing a shared community we’ve been a part of but just can’t manage the social energy required to commit to anything regularly on the weekend after a week of teaching high schoolers.

Working more as a society might feel like a zero-sum game, but the reality is that we don’t just “do more work”; we divert human energy away from other critical parts of life.

When a society simultaneously withdraws public support for social reproduction and conscripts the chief providers of it into long and grueling hours of paid work, it depletes the very social capacities on which it depends. This form of capitalism is stretching our “caring” energies to the breaking point.4

Lifters and Leaners.

If investing energy into care and connection to maintain social bonds is the glue that holds us together as humans when things start to fall apart, then who are the real freeloaders?5

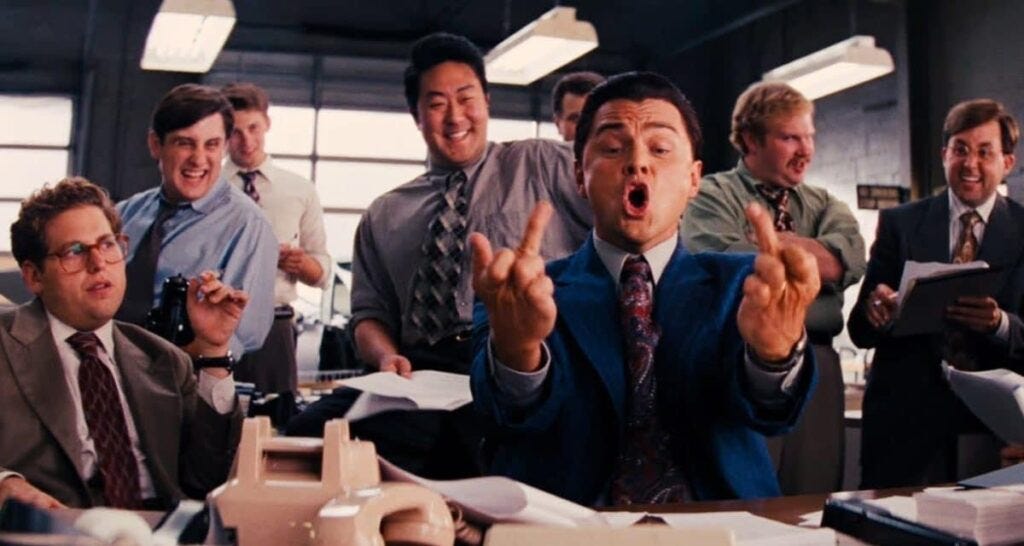

To lean on old tropes, could it be possible that the 70-hour-a-week 90’s stockbroker, who has no time or interest in anything beyond the vortex of corporate life, has actually been leeching for too long off the hard “glue-work” of his stay-at-home wife, the local volunteer librarian, and less busy friends who tend to the networks of care that keep everyone afloat and will tend to his grief when the market crashes?6

This is why commentary on “lifters and leaners” in society really riles me up.

Because if our only measure of contribution is economic, then certain members of society can get away with the absolute bare minimum of social contribution — often while perpetuating work cultures that leech endless hours and volumes of human energy away from families, neighbourhoods, collectives and communities.

This is not a diatribe against work, production, or having a career — but an acknowledgement that capitalism has no handbrake and f*cking steamrolls over anything that threatens to slow it down.

When it comes to prioritising the glue that holds the rest of life together, we’re swimming upstream. We have to fight, often without recognition, to do the barely visible work of deeply loving and caring for ourselves and one another. Unless we can begin to name the beauty and importance of connection, care, rest and play, we will continue to marginalise it.

Take care as always.

Chat soon,

Shane.

If you already have too many subscriptions, but want to support my writing as a one off, a lovely way to do that is:

If you want to follow along, or support Untethered ongoing, Subscribe or Upgrade here:

I love hearing your thoughts and reflections, feel free to:

If you want to get in touch, send me a message:

If you want to share this post, there’s a very helpful button called:

If you enjoyed this and want to see where we’ve been, start here:

It’s important to note here that I’m addressing a value system within our culture, not putting the boot in on everyone who has to work long hours. There are obviously plenty of scenarios where this is the only viable option, i.e. a low-wage parent being required to work multiple jobs and long hours to provide for their family. Instead, I’m trying to discuss the idea of long hours a mark of status, or as an aspirational symbol of career progression.

If you’d like to sit with me and argue that any of these things are fundamentally more difficult than your job when you take remuneration and social kudos away, I’m all ears.

Help with kids aside, I have friends who show up, check in, listen to despairing diatribes about fighting NDIS, or spend an evening doing nothing other than drinking and laughing at absolute silliness and nonsense because sometimes that’s all I need. I’ve learned a lot about friendship from very good friends and try to do the same for them.

Fraser: “This is very similar to the way that nature is treated in capitalist societies, as an infinite reservoir from which we can take as much as we want and into which we can dump any amount of waste. In fact, neither nature nor social reproductive capacities are infinite; both of them can be stretched to the breaking point. Many people already appreciate this in the case of nature, and we are starting to understand it as well in the case of “care.””

Again, I want to be careful here because there’s a danger of assigning value to human life according to what they can “do”. I firmly believe that all people are a gift, are innately valuable, and are worthy of respect, dignity and care regardless of their capacity to contribute through functional capacity.

I say all this knowing that as a man I wasn’t socialised to feel primarily responsible for so many elements of connection that make up the Living Human Web. I certainly haven’t resolved all of this, but as someone who has spent a long time working in care, being a part-time stay-at-home parent, fostering relationships of depth and vulnerability and doing difficult work on my interior life, I can attest to both the joy and effort that this has required.

Lovely connected moment of the week: my Kiwi friend popped over for a cuppa with her visiting mum. We sat around the table talking about things in that comforting understanding that can only come from a shared culture. Her toddler was getting into the Duplos and crushing on my youngest, while neighbourhood boys knocked on the door to throw airplanes with my oldest. Stuff like this rarely happens anymore, but it was precious and warm.

Great essay! Love the term “gross domestic napping.”