#5 - Mythic truisms and the marginalisation of care.

How believing the worst of each other becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Hi! 👋🏼

Before I get into things today, one quick thing:

If you’re a subscriber who receives this in email form, it’s worth knowing that, at times, I’ll chuck references or extra comments in the footnotes. Rather than scrolling to the bottom, the easiest way of seeing these is either by clicking the Untethered banner at the top to open it in your browser or by using the Substack app. This way, you can just hover your pointer over the reference number, and the content will appear. Hooray!

You can also share, and “restack” this piece if you think other’s might like it. Please feel free to send it around to anyone you think might be interested, it really does help get the word out.

If you’re new to this newsletter and want to read more, it might be helpful to start here.

Good times.

Shane.

Where the Window got its Magic.

Last post, I introduced you to the concept of The Magic Window — a cultural narrative that tells us we can make the most of our lives by freeing ourselves up for enjoyment, advancement and opportunity by minimising our entanglement in forms of giving and receiving care that involve mutual-obligation.

But where did The Magic Window get its magic? Why does the script it sells feel so familiar and powerful? As previously noted, it’s at least in part because it taps into primal emotions related to survival: fear and ambition.

This script teaches us to be afraid. To fear falling by the wayside. To cling to independence at all costs. It taps into our ambition and fear simultaneously:

-If I get ahead, I’ll be powerful.

-If I don’t, I’ll be vulnerable.

In some ways, they are two sides of the same coin. “Power” is a relative concept — you are only powerful by contrast to others who you might need to use your power against or those who might want to use theirs against you. In a world of “scarcity”, getting ahead means securing your future and lowering the risk of becoming vulnerable. By this logic, being powerful or resourced means being less vulnerable. Maximising your time The Magic Window makes a lot of sense.

I say “in a world of scarcity” in scare quotes deliberately because while on one hand, it is categorically accurate (there are finite resources in the world), on the other, it is also reflective of a particular view of human behaviour — that individuals are principally in competition with each other, that we act primarily according to our own best interests, and that nature flourishes according to “survival of the fittest”. When spelt out like this, the subtext is that we should fear vulnerability because we live in a world where we shouldn’t expect any help from others, yet we should expect that others will naturally take advantage of us given the chance.

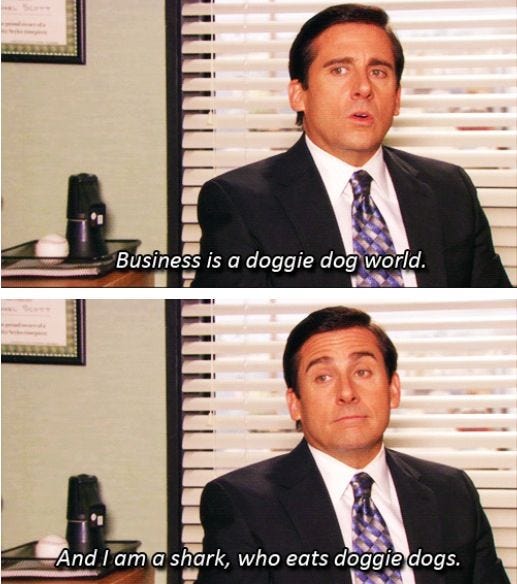

While we can all think of countless exceptions to these truisms, they have become such a fundamental part of our collective culture that they’ve taken on an almost mythic quality. I’ve heard people refer to them almost deterministically, as though they are the hand of fate: “It feels kind of mean, but we’re all in competition, right?” or “I don’t love the policy, but it’s survival of the fittest, I guess? 🤷🏻”

There is perhaps no more potent myth than the idea of a “self-made man” — a rugged individual who stared down the harshness of the world and, with a combination of grit and determination, single-handedly pulled himself up by his bootstraps and grew a multi-million dollar enterprise. Remember this guy, we’ll return to him later.

Mythic Truisms.

The truisms above operate in conjunction with a whole category of language whose origins largely go under the radar: “entering the workforce”, “stay at home mum”, “work/life balance”, and “Gross Domestic Product”.1 Language shapes our relationship to what it’s describing, and in this case, it sets our expectations for how humans should live. These phrases didn’t just drop from the sky; they are linked to two foundational cultural narratives that have come to work together: capitalism and evolution (albeit a very bad reading of the latter).

For those of you who aren’t particularly interested in economics, I’m not going to get into the weeds of that today, but I hope to help make sense of why this matters as we go. Most of you will know that capitalism is an economic theory. But I’m going to argue it’s far more powerful than that. It’s also become a social imaginary — which means that capitalism has colonised the way we imagine the world works.2

“People do this”, it tells us, “because this is how humans work.” As we see in the examples above, even if we don’t like the story (the hampster wheel of grind culture, for example), it has convinced us that it’s how everyone else works anyway, so we’re the suckers if we don’t do the same. It has become a self-fulfilling prophecy that uses the economic conditions it creates to ensure the story it tells comes true — leaving us to believe it was right all along.

But is it really how humans work? Or is it just how some humans work? Or is it partly how humans work because this is how they’re told humans work, and they now either feel justified working this way or terrified that if they don’t, they’ll be left behind? Or is it actually a grand magical illusion that completely ignores how the world actually works because it’s very inconvenient for certain people to acknowledge otherwise?

What if we’re actually missing half of the story? To answer these questions, I’m going to introduce you to the first of a number of women who have both shaped this project and changed my life in the process.

Deeper origins.

Once upon a time, I was convinced that at the heart of The Untethered Dillema was the tyranny of capitalism. I’m now convinced it runs much deeper than that — that the form of capitalism we have is actually an extension of a far bigger problem.3 The very good news, however, is that all is not lost. There is hope because within humanity are deep wells of resistance that have been practised for eons.

When researching for my thesis, I stumbled on this book by ethicist Dr Sandra Sullivan-Dunbar4 :

It’s brilliant, but as it’s a fairly dense academic text, it’s certainly not light reading. In it, she does something quite remarkable, which I’ll do my best to summarise here and unpack more fully in the future.

Dr Sullivan-Dunbar discusses our approach to Dependent Care Relations (DCR). DCR refers to the care of those who are dependent on us for survival and flourishing, such as children, disabled persons, and the aged. Another way of phrasing it would be “care obligations”, the forms of care you don’t really have a choice about if you are the one responsible for them. (I mean, you could just drop a kid off at the park to fend for themselves, but I hear it’s frowned upon.)

The key issue is “who is responsible for them, and what does society owe them?” Sullivan-Dunbar surveys the history of economics, philosophy, theology, political theory, ethics and a range of other critical disciplines and makes the argument that DCR have been marginalised in them all.5 Overlooked. Ignored. Devalued.

Because all of these disciplines don’t adequately address these forms of care, culturally, they are not perceived as a communal responsibility and instead fall to whoever is left carrying the can.

In a nutshell:

CARE HAS BEEN MARGINALISED.

CARE HAS BEEN MINIMISED.

CARE HAS BEEN DEEMED NON-ESSENTIAL.

“PROGRESS” HAS BEEN PROMOTED.

“PROFIT” HAS BEEN PRIORITISED.

“PRODUCTIVITY” HAS BEEN VALORISED.

What does this mean? It means that the very stuff that has kept us alive, and connected and in community has been segmented off and separated from a bunch of other stuff that has been deemed more important, namely that which allows us to “produce” and “consume”, accumulate wealth, compete, and get ahead.

Which, she argues, is really weird. Because:

We begin life ensconced within and dependent upon the body of another human person, using her body as a source of nutrients, oxygen, warmth, and space. When we emerge into the world as a separate body, we remain utterly dependent upon other human beings to feed us, to keep us warm, to hold us, to talk to and socialize us, to protect us from harm. We are bodily dependent again when we are sick, or when we are disabled, and if we live to old age, we are often dependent on others in the frailty of our final years. And at those points in our lives when we seem most autonomous, we nevertheless remain deeply dependent on others in countless ways that we often fail to acknowledge.

This is a polite academic way of saying: How f*cking dare anyone ignore this?

Human dependency is an unavoidable reality, and we each owe our very lives to the deep care of others. If we are going to continue as a species, we must recognise and prioritise care for each other. For Sullivan-Dunbar, this is not an inconvenient distraction from the task of being human; it is the very foundation of it.6

I’ll show in future newsletters how this has played out in various disciplines, but for now, I just want you to think about the womb we were all dependent on and the price paid by the body we lived in. About all the thousands of ways that body was supported and nurtured and cared for and fed and held during that time by hundreds of invisible faces, and then think about how that body is cared for and rewarded and promoted in the “workplace”, and thrust into an abundance of riches as a reward for its labour… oh, wait a minute. Nope.

It’s far more likely that this body will fall on the wrong side of nearly every statistic of economic advantage on offer, both now and in the future, for its foolish decision to take on this kind of burden in the first place.

“Care is painted as a low skill job that should fall to anyone not busy or important enough to avoid it.” — Me, quoting myself, like a true narcissist. From my last post.

Too many d*cks on the dancefloor (of the disciplines.)

But wait, why is care so often marginalised in the foundational texts of our disciplines? The answer often lies in the kinds of people who found themselves with the free time to sit around and theorise about how the world worked because their lot in life involved a lot more “work” and a lot less “care”.

The kind of people that weren’t bogged down with or even necessarily aware of who was choosing the kid's clothes, checking in on the sickly neighbour, tending to the elderly grandparent, breastfeeding through mastitis, or noticing that the butcher was looking depressed.

Spoiler alert: it was Dudes.

Not just any dudes. Dudes with spare time to think and write and ponder and not be interrupted by pesky children with annoying questions.7 Dudes who could make bold claims about the world by believing that all this “care stuff” just happened effortlessly in the background. A very particular kind of Dude who also wasn’t enslaved or stuck down the bottom of coal mines getting black lung and paid a pittance. A sausage sizzle of “self-made men” who had all that spare time to write about how we could all be more “productive” (in the case of economics), or more sacrificial (in the case of theology), or more “rational” (in the case of enlightenment thinkers, or more “civilised” (in the case of “explorers”) or more “fit” (in the case of evolutionary theorists). Dudes who were so busy theorising that they forgot to wonder where their dinner came from.

“Caregivers are the ghostwriters of economic success: their work subsidizes states, the private sector and households.” — Amy Hall, The Hidden Debt of Care.

Some of these Dudes, who shaped the formative years of the academic disciplines we study today, were willfully ignorant; others tried hard but fell incredibly short of engaging with the real world. Either way, too many of them remained almost completely oblivious to the fact that others were completely consumed in the incredibly complex, exhausting and difficult work of caregiving and fostering community.

Others who, if they had a spare moment, could have shown at length the kinds of efficiency, ingenuity and dedication required to care for kids and neighbours and parents and glum butchers all at once on a shoestring budget. Others, who, if they were socially positioned to, might have happily told them exactly how far up their ass they could shove their sermons about how to generously use your “spare” time and money when such a thing as “spare” did not exist for people drowning in care needs.

And so what kind of life did these self-made men conclude would really keep the nation advancing, the world turning, the wealth accumulating, the thinking progressing, and the spirituality spiritualising, and the ethics teaching us about what our real responsibilities were?

Exactly the same kind of life that we’ve been told will make our time in The Magic Window last forever if we play our cards right.

What a coincidence!

Before we go, I want to remind you of my promise that all is not lost. As dire as this short history sounds, it is crucial we do not fall into the trap of despair.

Remember: Care may have been marginalised, but care has persevered. And I will argue that to ask less of some means we need to ask more of everyone else.

“…the idea that you could build a society that assumes every adult is a person with primary care responsibilities, community engagements, and social commitments. That’s not utopian. It’s a vision based on what human life is really like.” - Nancy Fraser, interviewed in Dissent Magazine.

As always, I’d love to hear from you in the comments if you found any parts of this helpful or want to add your perspective.

Take care,

Shane.

If you already have too many subscriptions, but want to support my writing as a one off, a lovely way to do that is:

If you want to follow along, or support Untethered ongoing, Subscribe or Upgrade here:

I love hearing your thoughts and reflections, feel free to:

If you want to get in touch, send me a message:

If you want to share this post, there’s a very helpful button called:

If you enjoyed this and want to see where we’ve been, start here:

Much like my earlier references to “spending time”, seeing relationships as “assets and liabilities”, and managing people as “human resources”.

It’s also worked to colonise a lot of other things, but as always, more on that later. Also, I came across this idea via Bruce Rogers-Vaughn, but there will be lot more on him in the future.

Those of you who are into economics may be wondering why I haven’t referred to neoliberalism yet. I‘m choosing not to for the moment because I’m already introducing a lot of new ideas to readers without muddying the waters further. Also, the issues I’m addressing are primarily rooted in neoclassical capitalism, from which neoliberalism has grown. Once you see them in capitalism, it will become clear how they play out in the hegemony of neoliberalism in accelerated forms.

You can read more about Sandra Sullivan-Dunbar if you google her. For now, you just need to know: a) She’s an Associate Professor of Christian Ethics at Loyola University, Chicago, where she teaches feminist ethics, social ethics and sexual ethics. b) She wrote a book that became a primary text in my thesis, and c) She’s rad.

The text focuses primarily on “Dependent Care Relations”, but it’s also connected to the idea that dependency on others is a reality for all of us and that there are both deep connections and blurry lines between these specific forms of care and the care we all require to flourish.

“…the idea that you could build a society that assumes every adult is a person with primary care responsibilities, community engagements, and social commitments. That’s not utopian. It’s a vision based on what human life is really like.” - Nancy Fraser, interviewed in Dissent Magazine.

Btw, this post is not anti-men. It’s anti-patriarchy. I am a man. I know and love many great and caring men. But I am also absolutely exhausted by men who don’t have the first clue about what care really costs, lecturing caregivers on how to succeed in life when they’ve been bludging off the care of others for a lifetime. I acknowledge my own blind spots in this — there are things I will never truly understand because of my place in the world, but I am committed to continue learning.

This is interesting to me Shane in terms of my relationship to the care my 90 year old mother needs. She is in a nursing home and the staff are overwhelmingly from cultures where elders are loved and respected and not in nursing homes. My mother is hard for me to be around for so many reasons and I'm very grateful for the care she receives there. Caring for the vulnerable is very unsexy, confronting and not part of the package of abundant life I was sold in shiny Christian spaces where everyone was glamorous and triumphant. It also necessitates slowing down and accessing patience, grace and an override of what I'd rather be doing. We are going to need each other more and more as systems collapse which feels both uncomfortable and hopeful.

Thank you for writing this, it's very interesting. I am someone who has many people depending on me for care in my family, and it's nice that people might just be starting to realize that this is valuable! I also work for that necessary for living money as a support worker/caregiver, as I've mentioned before, so I guess I like to double down on caring for people!