#4 - Out of the frying pan and into the void.

The story of an interesting theory taking an unexpectedly autobiographical turn.

If you’re new to Untethered, it might help to start here.

And in case you missed it, there’s now an Untethered Instagram page - it’ll be a pretty low-key affair, but feel free to follow along.

Also, a heads-up: this is a slightly heavier one.

I didn’t have long.

Last night, in a matter of minutes, an ordinary evening turned into a shitshow, another kind of all-too-common ordinary evening. The Not Good kind.

I had to start making calls and find backup. Our family has 30ish people who keep us alive in various ways. Because time was limited backup had to be someone who already knew our immediate context and lived within a couple of kilometres. Two of my go-to’s got the call:

“Hey. Sorry, I don’t have time to talk. I might need you here in 25 mins. To stay for 45 mins… until the first one is asleep. I’ve got a couple of options, but I need to know within 5. Sorry!”

My wife had arranged a rare night out, so the two boys (eight and five) were with me and a support worker (SW). Things can escalate quickly in our house, and as hard as it might be to believe, a 2:2 ratio isn’t always enough to keep everyone safe. Our oldest is ADHD, autistic and has a profile called PDA, a serious nervous system disability which makes it incredibly difficult for him to regulate his emotions. He requires extremely high levels of support, co-regulation and accommodation. The meltdowns each day involve screaming, begging, violence, sobbing, and high levels of distress. They can range from minutes to hours.

Throw in a five-year-old who has lived with this his entire life and has naturally adapted mechanisms which allow him to cope with trauma and get the care he needs. I’m not sure I can adequately describe how intense each day is. Somehow this is all made more difficult by how immensely kind, empathic and delightful they both are when they can access regulation.

Last night it kicked off between the boys in a way that spelled danger. There was no way of dealing with it without our SW hastily removing our youngest from the property. This allowed me to start the process of slowly making space for our eldest to regulate while minimising the chances of anyone getting hurt.

There was no guarantee things would be under control before the end of the SW’s shift. It was either phoning for help or calling my wife back from her break — which is the equivalent of someone throwing a cup of iced water on your face just as you’ve fallen peacefully asleep after a 15-hour shift. The ice bucket challenge no one asked for: not cool.

With nerves fried — from too many years of being overstretched at home while simultaneously screaming into the void advocating for the kind of support which might actually give us a slim chance of keeping our family together — asking friends for help (for the millionth time) is something I can barely muster the strength to do. But tonight it’s the best in a range of shit options.

Wind back ten years: I was working two jobs I loved, going to gigs, and riding my bike around with my wife from pub to pub on warm summer evenings. I had started thinking about how community, care, and managing crises might look in a context where everyone appeared to survive, despite having so little stability. As someone so used to offering care, I certainly never anticipated it would be my life that depended so heavily on others answering my cries for help.

“Inner City Pressure”

In my earlier post, I discussed moving from a small city in New Zealand to the inner North of Melbourne:

“It was fluid, fun and full of characters. There were always new people to meet. Everyone had an interesting side project. And just as you got to know someone, they were moving to New York or Berlin.

I had gone from somewhere where you knew everyone’s history to a place where you could reinvent yourself every other weekend, and no one batted an eyelid.”

As fun as it was, it was in this context I first began to wonder what would happen to people if their lives took a turn for the worse.

“…in time, the shadow side began to reveal itself. I witnessed the underside of this kind of fluidity — people who felt unseen in crisis, who lived large but were flat broke, who struggled to find friendships that still held intimacy when everyone was sober. I watched friends hit rough patches and suddenly but reluctantly move hundreds of kilometres back home — while others wished they had a family to return to.”

In truth, I was worried for them. Some of it was surely just culture shock — I wasn’t used to people coming and going, casually announcing they were leaving next week and vanishing from our lives. While a part of me longed to be that casual and fancy-free, it also scared me. The friendship and affection were real but the stakes were perilously low.1

While I joke about “inner-city pressure” causing these dynamics, there’s plenty of data to show these patterns have been creeping into life all over the place for some time. With the rise of loneliness, there are fewer people we feel we can depend on in a crisis and we struggle to find people we feel safe enough to be vulnerable with. It seems our collective sense of community is under threat across the board.2 Philosopher Charles Taylor believes this is an ongoing fallout from “the great disembedding”. More on that later.

In New Zealand I was secure, immersed in a rock-solid, albeit sometimes claustrophobic community. I knew who would show up for me and I for them. Here it felt like life was a sitcom with a permanently rotating cast, absent a core set of characters.

So, leaving is bad right?

This might sound like I’m arguing everyone should stay put — the answer to the crisis of community is simply to live with whatever/wherever the universe has decided…

I’m not arguing that.

I don’t think we always can, even if we want to.

My other work involves supporting people who are survivors of coercive leadership practices and high-control religious spaces — often resulting in mental, emotional and bodily harm and various forms of ongoing trauma. The capacity to leave harmful communities, collectives, and relationships is fundamentally important.

In addition, moving to a context where we are able to flourish, live as authentic versions of ourselves, and take up opportunities which might make our lives better (or, at least provide the chance of survival). Queer kids growing up in homophobic towns, people of colour experiencing racism, neurodivergent folk given no room to thrive, members of dysfunctional family systems who need an ocean between them and their kin, workers stuck in dying industries. There are countless examples of needing to uproot to flourish.

As critical as I am of capitalism, I am unapologetically in favour of the fact that, for some, it has enabled them to escape coercion, poverty and oppression. Untethering from a community is a luxury for some, a compromise for others, and a necessity for many.

But there is a problem with the accounting. We don’t always consider what it might cost us each time we uproot. So many people who escape coercive forms of community initially feel a rush of freedom only to realise the way we structure autonomous individualism carries a whole different set of problems. Navigating a safe middle ground is complicated when your trust has been betrayed. So, we leap out of the frying pan only to find ourselves in the void.

The script we live with approaches “opportunity” as a net good but — and you’re never going to believe this /s — while a fluid workforce is great for capitalism, it can present huge challenges for forming community.

When we treat the world as an interchangeable backdrop to our lives as the main character, we can easily miss the fact that human flourishing most often depends on a network of relationships marked by trust, care, knowledge and the only phrase scarier to say aloud than “candyman”: mutual-obligation. It turns out we are more terrified of social debt than financial.

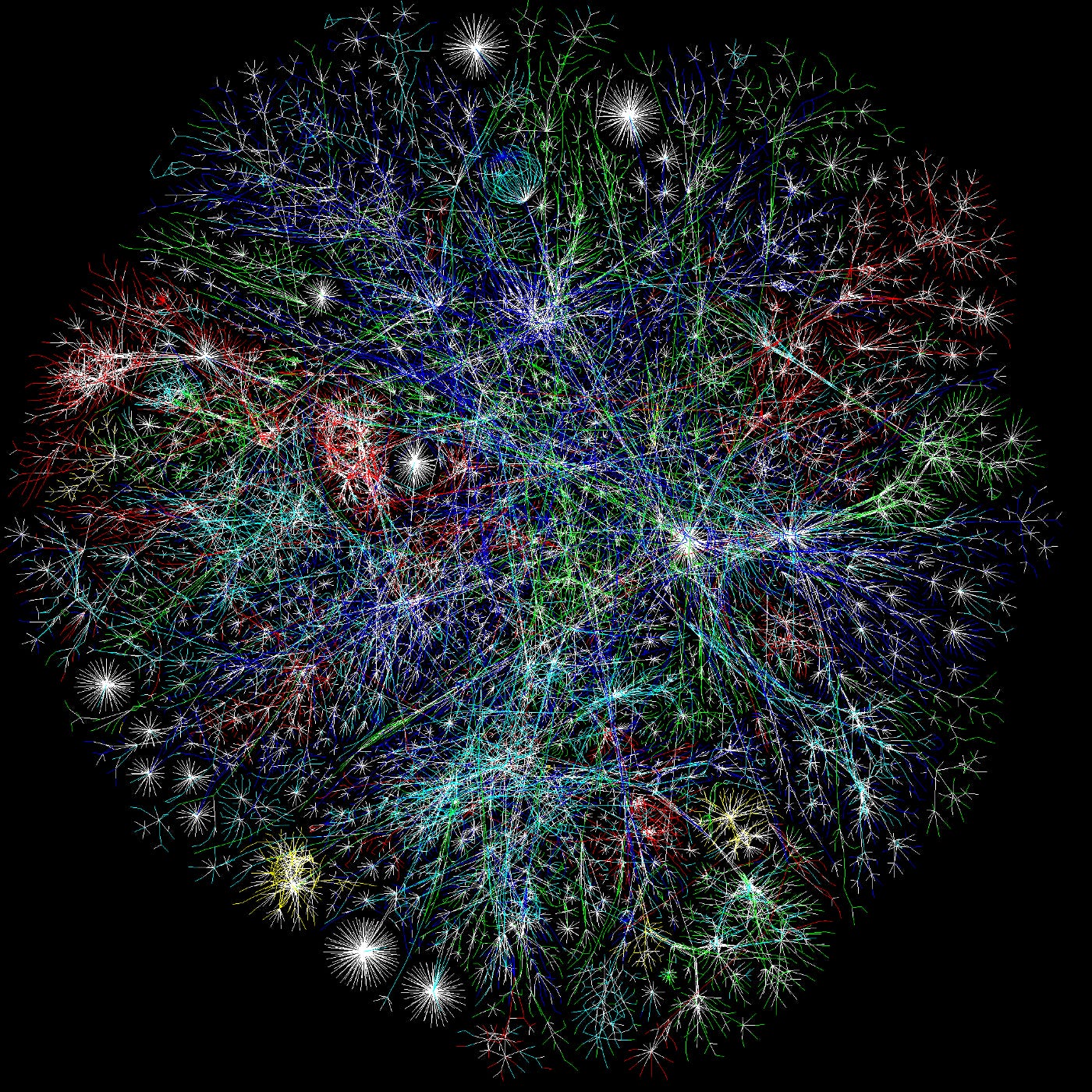

This network of care is known as “the living human web”, and it stretches beyond just our most intimate relationships to include various forms of connection we might not readily notice but play a surprising role in the well-being of society. The pensioner you chat to each Friday in the library without knowing you’re one of their few points of human contact in a week; the woman at the butcher who quietly pops an extra couple of chops in the bag because she can tell money’s tight at the moment; the single friend who helped raise your kids and became part of your family and now has to act happy for you when you excitedly announce you’re moving to Argentina next month.

There are forms of care that can only grow in time. Like knowing the difference between when “I need space” means “I need space” and when it means “I’m scared I’m not worth the time, or that you’ll be able to handle me up close, so I’m saying I need space, but I really wish you’d ask a second time.” This can’t be formed overnight. And sometimes, by the time we realise we need it, it feels too late to begin.

While we are trained to make our calculations primarily on what we have to gain from the arrangement, it’s not just our flourishing that depends on our connection to the living human web but the many people who are connected to us through it. We’ve been sold a story that while care matters, it’s optional. Avoidable. An afterthought. Care is painted as a low-skill job that should fall to anyone not busy or talented enough to avoid it. (Now, where could that have come from?) Yet, if depending on others, really depending on them, becomes a necessity for any of us, an Untethered life just isn’t enough.

Fluid community is great at triage — if you get your appendix out, feel sad for a bit, or have to dump a terrible boyfriend, there’s plenty of care on tap. But if it lasts for longer than a few months or means we can’t go to brunch or messes with people’s plans, it often feels too much to ask.

Relationships are assets, and should offer something back.

Some relationships are liabilities. Reconsider this investment.

After all, everyone is responsible for their own problems,

why should you be burdened by other’s ineptitude?

-from Congratulations!

If coercion is more likely to happen in a context of stability where it’s difficult to leave, then abandonment is more likely to happen in a context where everything is fluid. Is there a third way that might offer safety and care? Empowerment and connection?

Currently, my family needs the care of around 30 kind souls just to make it through a month. And that’s just for direct care. It doesn’t count the endless ways in which kindness, love and practical concerns are met by people who don’t even know our name.3

As a society, we may have slowly lost the muscle memory of forming community, but that doesn’t mean we can’t relearn it.

The Magic Window

What I’ve realised is that the neoliberal promise of “try hard enough, and you can remain independent and have it all” works relatively well as long as nothing goes wrong for you or anyone you’re obliged to keep alive. So we go to sleep each night just hoping that we’ll be ok and working our asses off to make sure we can pay for what we need if not. Or, we might put all our eggs in the basket of a stable relationship, depending on them to be our lover, best friend, social safety net, and backup plan as our world shrinks around us.

I’ve called this “The Magic Window”, the illusory period of time where we get to live what we’re promised is “the life” — the carefree years experienced between being dependent on care in our childhood and either having to offer it or depend on it later down the track. These are the years where we are encouraged to make our mark, climb the ladder, experience the world, hustle and grind — storing up credits in status, networks, career progression, and net worth.

Central to this narrative is the idea that there is nothing scarier than being tied down, or making yourself vulnerable, or needing to depend on anyone or even causing so much as a mild inconvenience to someone else’s plans. And without ever formally signing up for it, we are unwittingly committed to a shared social contract that works against our very humanity. It is cutting us in two: we are longing to feel grounded, but terrified of being bogged down.

It’s not just individuals who are vulnerable to this script; there’s a version of it that applies to nuclear families as well. However, my experience is that just under the surface, particularly in the early years, there’s often a quiet desperation — the loneliness of feeling like you’re living in a different time zone to Untethered friends, the desperation of long hours of care in trying circumstances without a break, and the cruelty of imbalanced gender expectations concerning “work” and care.

All of this madness is built on some “very important indisputable facts™” about humanity: individuals always choose according to self-interest, we are ultimately in competition with one another, we live in a world of scarcity, and the true hero of our world is a strong man who gets shit done.

Spoiler alert: these are not, in fact, facts or common sense; they are absolute bullshit with a level of toxicity for our future survival that is difficult to describe without foaming at the mouth and “just so happen” to fit with a narrative that suits the economic engine that drives Western “progress”.

This script teaches us to be afraid. To fear falling by the wayside. To cling to independence at all costs. It taps into our ambition and fear simultaneously:

-If I get ahead, I’ll be powerful.

-If I don’t, I’ll be vulnerable.

We have to believe there are better stories to live by. Better for all of us.

About last night.

This project began primarily as a series of wonderings, an academic exploration into what made the world the way it was. To be honest, some part of me would have preferred it stayed there. I never intended it to become quite so autobiographical. But here we are.

And last night, we got the help we needed. We made it. We live to fight another day. (Unfortunately, that’s more literal than I’d like it to be.)

We are still here. Forever grateful for the myriad ways we are held together by others. In turn, we continue to offer care as best as we can. Apparently, even when pushed to our limits, we still have something to give to the outside world. Kind words, late-night condolences, a shared meal, surrealist comedy routines performed by sugar-fueled minors… it’s not much, but you’d be surprised what nourishes the living human web.

We may need more than we’d ever imagined, but it’s not as scary as I once thought. It turns out there’s life on the other side of the Magic Window.

Take care,

Shane.

If you already have too many subscriptions, but want to support my writing as a one off, a lovely way to do that is:

If you want to follow along, or support Untethered ongoing, Subscribe or Upgrade here:

I love hearing your thoughts and reflections, feel free to:

If you want to get in touch, send me a message:

If you want to share this post, there’s a very helpful button called:

If you enjoyed this and want to see where we’ve been, start here:

I realise I am making sweeping generalisations to show a pattern here. There were, of course, numerous people connected to networks and communities that were notable exceptions to this: including queer “chosen families", which I’ve learned a lot from and we will look to later on.

“Another way of measuring friendships is to look at reciprocal friendships. Here, the Australian surveys asked: 'How many people are there around here to whom you can turn in times of difficulty? I mean, someone you could trust, and whom you could expect real help from in times of trouble (apart from those at home?' In 1984, the average adult had five of these reciprocal friendships. By 2018, it was down to three. Since 1984, Australians have shed four of the friends they can talk with frankly and lost two of the friends who would help them in times of trouble. On these measures, Australians today have only about half as many close friends as in the 1980s” from Andrew Leigh and Nick Terrell’s “Reconnected”.

Including the “tax system”, which needs a serious rebranding effort to acknowledge all the ways in which it functions as a crucial element of care for the common good. Would corporations then feel bad for evading it? Probably not. But it might help us turn up the heat on what we expect from them.

I'm just an internet stranger, but I appreciate every word you've written here. And I'm glad you got through that night.

As someone currently in the "Magic Window", and with exactly zero true, can-call-at-3am-if-shit-hits-the-fan reciprocal friendships (apart from my husband and my Mum), I worry about the future. I'm sure there are many people like me, who in order to maintain employment, are left with no time or energy to foster outside relationships and build community. But by being a good little economic unit in the meantime, hopefully I can pay for whatever support I might need down the line. Or maybe I'll be lucky enough to experience a different kind of window after I retire, when for a few years I might be able to take the energy previously used for work and direct it outwards towards others instead, and build community then.

This is going to sound kinda bleak, but I think this gets at something behind the reasoning for David Seymour's euthanasia bill here in NZ (for the record, I despise everything that man stands for, but I do support people having the choice to end their lives when faced with sickness or pain that has no hope of ending or being fixed). But it neatly solves the "problem" of untethered people who reach the end of their economic viability, and would then only become a "drain on the system". Which I think was his true reasoning for bringing that bill into law. This aspect of late-stage capitalism makes me extremely uncomfortable.

So that was a bit of a ramble, but I just wanted to say thanks for your writings. It must be hard to find the time for it with all the homelife goings-on. But it is appreciated :-)

Beautiful. As someone who has found themselves in the “needier than I would have ever deemed acceptable” space of life and limitations, I am continuously grateful for those in my life who step into the gaps and I try to remember I also have beautiful things to offer those who I am in mutual-obligation with.